Introduction to Sustainable Fashion

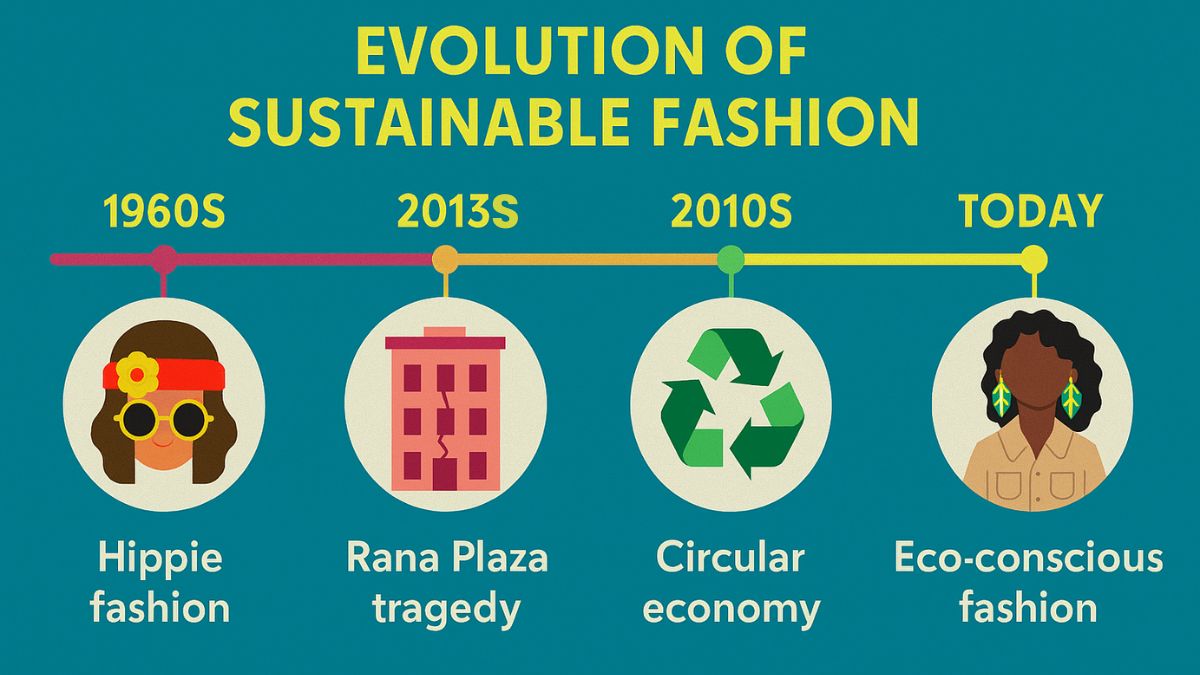

When did sustainable fashion start? This question has become increasingly vital as more consumers and industry players recognize the importance of environmentally and socially responsible clothing production. Sustainable fashion refers to clothing that is designed, manufactured, distributed, and used in ways that are environmentally friendly and socially responsible. But contrary to popular belief, the movement didn’t emerge overnight. The roots of sustainable fashion stretch back much further than most people realize, with evolving concerns and approaches that have shaped today’s landscape.

Understanding when sustainable fashion started requires examining multiple interconnected threads: environmental awareness, labor rights, material innovation, and changing consumer behaviors. From early counterculture movements to tragic industry wake-up calls and groundbreaking technological innovations, the history of sustainable fashion is as complex as the supply chains it seeks to transform. This comprehensive timeline will explore the key moments, pioneers, and movements that have defined sustainable fashion throughout history and examine how these developments have shaped the industry we know today.

The significance of tracing this history goes beyond mere academic interest. By understanding where sustainable fashion came from, we can better comprehend where it’s headed and how we might contribute to its future. As we delve into this rich history, we’ll discover that sustainable fashion is not a passing trend but rather an evolving consciousness that has been building for decades, with each era adding new layers of understanding and innovation to this critical movement.

The Early Roots: Before “Sustainable Fashion” Was a Term

Pre-Industrial Clothing Practices

Long before the term “sustainable fashion” entered our lexicon, clothing production operated very differently. In the pre-industrial era, specifically during the 1700s-1800s, clothing was predominantly handmade and created using locally sourced materials. This meant production occurred on a much smaller scale, significantly reducing environmental impact compared to today’s standards. The use of natural fibers like wool, cotton, and linen was widespread—materials that were biodegradable and didn’t harm the environment. Perhaps most importantly, clothing during this period was valued differently: garments were repairable and often passed down through generations, dramatically reducing waste through practices we would now call “circularity”.

This era represents what some might consider a naturally sustainable approach to fashion, not by choice but by necessity and limitation of technology. The connection between clothing producers and consumers was more direct, and the environmental impact of garments was minimal compared to today’s standards. The slow fashion principles that modern advocates promote hearken back to this era when clothing was made to last, valued for its durability, and rarely discarded without attempts at repair or repurposing.

19th Century Influences and Early Concerns

The Industrial Revolution (approximately 1760-1840) marked a dramatic turning point in fashion production. The introduction of mass production methods and the creation of synthetic fibers fundamentally changed how clothing was made and consumed. While this revolution made clothing more accessible and affordable to growing urban populations, it also sowed the seeds of many current environmental problems.

The shift toward cheaper, faster production methods laid the groundwork for what would eventually become fast fashion. Even at this early stage, concerns about the environmental impact of the fashion industry were raised, though these voices remained largely unheard amidst the enthusiasm for industrial progress. The rise of synthetic fibers, while revolutionary in their durability and cost-effectiveness, began the industry’s long and complicated relationship with materials that would prove environmentally problematic.

The technological advances of this period also created the conditions that would lead to the globalized, disconnected supply chains we see today. The separation between clothing producers and consumers widened, and the understanding of a garment’s full lifecycle became increasingly obscured. These changes, while not immediately recognized as problematic, established patterns of production and consumption that sustainable fashion advocates would later work to counter.

1960s-1970s: The Dawn of Environmental Consciousness

The Rise of Environmental Movements

The 1960s and 1970s marked a critical turning point in environmental awareness that would eventually influence the fashion industry. The publication of Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking book Silent Spring in 1962 is widely regarded as a pivotal moment that raised public awareness about the destructive impact of pesticides and toxic chemicals on the environment. This book, along with the establishment of environmental organizations like Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth, helped spark a global environmental movement that would eventually turn its attention to fashion’s impacts.

During this period, we also saw the establishment of The Nature Conservancy in 1951, which arguably marked the beginning of modern environmentalism in the United States. These developments created a foundation of environmental concern that would eventually extend to examining the fashion industry’s practices. While sustainable fashion as a defined concept hadn’t yet emerged, the broader environmental consciousness being raised during this era set the stage for later scrutiny of fashion’s environmental footprint.

The first Earth Day in 1970 further symbolized the growing mainstream recognition of environmental issues. This emerging ecological awareness began to influence consumer behavior and expectations across various industries, including fashion. People were starting to ask questions about the products they bought and their broader impact on the world—questions that would eventually transform how we think about clothing.

Counterculture Influence: Hippies and Punks

The late 1960s and 1970s witnessed the emergence of influential subcultures that would challenge mainstream fashion consumption. The hippie movement embraced natural fabrics, handmade items, and a simpler way of life that directly rejected mass consumerism. Their preference for locally-grown, handmade, and pesticide-free products represented an early form of conscious consumerism.

Following the hippies, the punk rock movement of the mid-1970s introduced its own sustainable practices, though for different reasons. Punks embraced secondhand clothing, vintage pieces, and upcycling as expressions of rebellion against conventional fashion and social institutions. Their DIY approach to fashion meant rewearing and customizing existing garments rather than buying new—practices that sustainability advocates now promote as solutions to fashion waste.

Both movements, despite their different aesthetics and motivations, shared a rejection of mass consumerism and the dominant ideas of traditional fashion. They established alternative relationships with clothing that valued individuality and rejected disposable fashion trends. These subcultures planted important seeds that would later grow into more defined sustainable fashion movements, demonstrating that clothing could be used as a form of protest and expression beyond mere trend-following.

1980s: Subcultures, Thrifting, and Early Pioneers

Subculture Movements and Thrifting Culture

The 1980s saw the continuation and evolution of subculture influences on sustainable fashion practices. The punk rock movement, which had emerged in the mid-1970s, gained momentum and made vintage shopping and thrifting increasingly fashionable. What began as a form of rebellion against social norms and capitalism gradually influenced mainstream fashion perceptions, making secondhand clothing a legitimate style choice rather than merely an economic necessity.

During this decade, the concept of upcycling—transforming old or discarded materials into something new and valuable—became more common within these subcultures. While the term itself wouldn’t become popular until much later, the practice of customizing and reinventing secondhand clothing became a creative outlet for those outside mainstream fashion. This decade demonstrated how subcultures could drive sustainable practices through fashion rebellion, laying the groundwork for the upcycling trend that would gain commercial traction decades later.

The lasting impact of these subcultures can be seen in today’s thriving secondhand market. The acceptance and even celebration of vintage clothing that these groups pioneered has evolved into a multi-billion-dollar industry. By rejecting newness as the ultimate value in fashion, these movements established an alternative aesthetic that continues to influence sustainable fashion today.

Early Pioneers and Ethical Campaigns

The 1980s produced several key figures and movements that would shape sustainable fashion’s development. In 1989, political activist and designer Katharine Hamnett began her pioneering research into the fashion industry’s socio-ecological impact. Her work represented one of the first systematic attempts to understand and communicate fashion’s environmental footprint, setting an important precedent for future designers and activists.

Hamnett is credited as being one of the first designers to work with distressed denim and organic cotton, consciously choosing materials with lower environmental impact. Her political activism through fashion—most famously her slogan t-shirts—demonstrated how clothing could be a medium for environmental and social messages. This approach connected fashion with activism in ways that would inspire future generations of sustainable designers.

The late 1980s also witnessed the emergence of the anti-fur movement, which marked early efforts to promote animal rights within fashion. These campaigns gained significant traction and would eventually become part of popular culture in the following decade, with numerous celebrities joining the cause. The anti-fur movement represented an important early connection between ethical concerns and fashion consumption, establishing a template for future consumer activism around fashion ethics.

Key Sustainable Fashion Pioneers (1980s-1990s)

| Pioneer | Contributions | Period |

| Katharine Hamnett | Early research on fashion’s ecological impact; political activism through fashion, use of organic cotton | Late 1980s |

| People Tree | First Fair Trade fashion label; focus on people and environment throughout supply chain | Founded 1991 |

| Patagonia | Pioneer in recycled materials (transforming plastic into fleece); switched to organic cotton (1996) | Early 1990s |

| Stella McCartney | Luxury designer emphasizing sustainability and animal rights | Late 1990s |

1990s: Fast Fashion’s Rise and Sustainable Responses

The Birth of Fast Fashion

The 1990s marked a pivotal moment in fashion history with the rise of fast fashion as we know it today. The term itself was coined by the New York Times to describe Zara’s revolutionary production model, which could take designs from concept to store shelves in just two weeks. This accelerated production system represented a dramatic shift from traditional fashion cycles and would fundamentally change how people consumed clothing.

This decade saw the outsourcing of production to lower-wage countries snowball, as brands sought to take advantage of reduced labor costs. While this made clothing more affordable for consumers, it also led to a surge in worker exploitation and further disconnected consumers from the people who made their clothes. The globalization of fashion supply chains accelerated, making transparency and accountability increasingly challenging.

The rise of fast fashion created a dichotomy that would define the following decades: as the fast fashion industry grew, so too did concerns about its social and environmental impact. This tension between convenience, affordability, and ethics became increasingly apparent. The same decade that gave us ultra-fast, disposable fashion also saw the emergence of organized responses in the form of sustainable fashion pioneers and watchdogs.

Pioneering Sustainable Brands and Growing Awareness

Despite—or perhaps because of—the rise of fast fashion, the 1990s also witnessed the emergence of dedicated sustainable fashion pioneers. In 1991, People Tree was founded by Safia Minney in Tokyo, Japan, as one of the first fashion brands created with deep concerns for people and the environment. The company began by making handwoven and naturally dyed handbags and clothes, launching its first clothing collection in 1997 using eco-friendly and sustainable fabrics .Another standout brand, Patagonia, began seriously evaluating its environmental footprint during this decade. The outdoor clothing company became the first in its category to transform plastic into fleece and, in 1996, made the switch to exclusively using organic cotton. These moves demonstrated that substantial companies could make meaningful changes to their material choices and production processes.

The 1990s also saw growing consumer awareness of social injustices in fashion, including the use of sweatshops and child labor. High-profile scandals, such as Nike’s low-wage factory controversies in 1991, brought media attention to labor conditions in garment factories. These controversies began to influence consumer consciousness and created pressure on brands to be more accountable for their supply chains.

2000s: Slow Fashion Movement Gains Momentum

The Slow Fashion Response

The 2000s witnessed the formalization of a direct counter-movement to fast fashion: slow fashion. The term was coined in 2007 by author and activist Kate Fletcher as an alternative to the increasingly accelerated fashion system. As Fletcher described it in The Ecologist: “Slow fashion is about designing, producing, consuming, and living better. Slow fashion is not time-based but quality-based (which has some time components). Slow is not the opposite of fast – there is no dualism – but a different approach in which designers, buyers, retailers, and consumers are more aware of the impacts of products on workers, communities, and ecosystems”.

This period saw fast fashion brands continue to flourish, but simultaneously, a cultural shift toward ethical and sustainable fashion was accelerating, aided by the growing accessibility of information on the internet. Consumers were becoming increasingly able to research brands’ practices and connect with like-minded individuals to share information and strategies for more conscious consumption.

The slow fashion movement emphasized several key principles that would become central to sustainable fashion discourse: quality over quantity, awareness of production impacts, valuing garments throughout their lifecycle, and recognizing the connections between fashion choices and broader social and environmental systems. This represented a significant maturation of sustainable fashion philosophy beyond simple material choices or individual ethical issues.

Key Organizational Developments

The 2000s saw the establishment of several important organizations and certifications that would provide structure and standards for the growing sustainable fashion movement. In 2002, the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) was formed as an internationally recognized textile processing standard for organic fibers. This certification ensured high-quality, safe, and sustainable organic fabric for consumers by setting stringent standards covering processing, manufacturing, packaging, labelling, trading, and distributing of textiles.In 2007, the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) was formed, beginning as a global alliance of over 200 members, including retailers, brands, suppliers, advocacy groups, academics, and labor unions. Their mission was to create “an apparel, footwear, and home textiles industry that produces no unnecessary environmental harm and has a positive impact on people and communities”. This coalition represented an important step toward industry-wide collaboration on sustainability challenges.

Other significant developments included the establishment of the Fair Trade USA ethical fashion certification label in 2011, which gave consumers confidence that products were made in safe working conditions by workers treated fairly and paid adequately. These organizational developments provided much-needed structure and verification systems that helped distinguish genuine sustainability efforts from mere marketing claims.

2010s: Tragedy, Transparency, and Transformation

The Rana Plaza Tragedy and Fashion Revolution

In response to this tragedy, Fashion Revolution was founded by Carry Somers and Orsola de Castro. This non-profit global movement campaigns for systematic reform of the fashion industry with a focus on greater transparency in fashion supply chains. The movement established Fashion Revolution Day on April 24 to commemorate the Rana Plaza tragedy, an observance that continues annually.

The disaster and subsequent activism created what many describe as a “before and after” moment for the fashion industry. For the first time, many consumers understood the direct human cost of their clothing, and the term “fashion revolution” became a rallying cry for change. The tragedy sparked a wave of sustainable and ethical initiatives and the founding of many more brands with sustainability at their core. Concepts like the circular economy gained mainstream attention as the industry searched for alternatives to the destructive linear model.

Documentaries and Increased Consumer Awareness

The 2010s saw sustainable fashion reach broader audiences through powerful documentaries and media coverage. The 2015 documentary ‘The True Cost’ provided a devastating look at the social and environmental impacts of the fast fashion industry, reaching viewers worldwide and dramatically increasing awareness of fashion’s hidden costs. The film’s release at the Cannes Film Festival, coinciding with Fashion Revolution Day, helped amplify its message.

During this period, books and films further exposed fashion’s secrets, embedding knowledge of the industry’s problems in the collective consciousness. As information became more accessible, buyers grew more informed about brands’ actions and values, and began using this knowledge to make more conscious purchasing decisions. This increased transparency put pressure on even high street and luxury brands to release “eco” collections and other sustainable initiatives.

The latter part of the decade saw significant developments in circular fashion initiatives. In 2017, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation released its ground-breaking report ‘A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future,’ which outlined the catastrophic results of the conventional linear production system and proposed a vision for a circular economy. This report would lay the foundation for a regenerative and restorative fashion industry and inspire numerous brands to commit to circular principles.

2020s: The Current Sustainable Fashion Landscape

Demand for Transparency and Accountability

The current decade has witnessed an unprecedented demand for transparency from fashion brands. Consumers increasingly call for greater accountability, with ethics and sustainability becoming key factors in purchasing decisions. This shift is particularly pronounced among younger generations, with McKinsey’s State of Fashion 2022 report noting that 43% of Gen-Zers actively seek out companies with solid sustainability reputations.

This increased consumer awareness has been accompanied by growing skepticism toward greenwashing. As consumers become more educated about sustainable materials and production methods, they’re also becoming more adept at identifying empty sustainability claims. This has created pressure for brands to provide concrete evidence of their environmental and social credentials rather than vague marketing language about being “green” or “eco-friendly.”

The 2020s have also seen a dramatic increase in fashion transparency legislation across various regions. The European Union has been particularly active in proposing and implementing regulations that require fashion companies to operate more sustainably and transparently. This regulatory pressure, combined with consumer demand, has made sustainability less of a niche interest and more of a business imperative for fashion brands of all sizes.

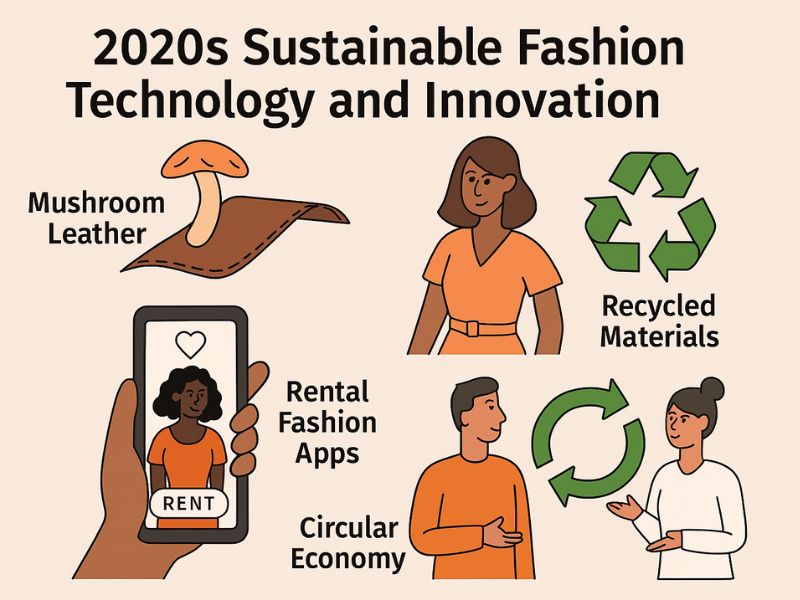

Innovation in Sustainable Materials and Business Models

The current sustainable fashion landscape is characterized by remarkable innovation in sustainable materials. We’re seeing increased use of biodegradable materials and leather alternatives, reflecting growing consumer preference for eco-friendly and ethical fashion options. Brands are exploring everything from mushroom leather and pineapple leather to fabrics made from algae, coffee grounds, and other unexpected materials that reduce reliance on conventional, environmentally damaging options.

Circular business models have also gained significant traction. The resurgence of thrifting and second-hand shopping, especially among younger generations, represents a major shift in consumption patterns. In 2021, 42% of millennials and Gen Zers stated they were likely to buy secondhand clothing, and approximately one-fifth of UK consumers reported buying clothes from sustainable brands. The global fashion resale market is expected to grow 127% by 2026, indicating the lasting power of this trend.

Fashion rental services have also expanded dramatically, with companies like Hurr Collective being dubbed “the Airbnb of fashion” by Forbes magazine. These models allow consumers to access variety and novelty without the environmental cost of new production, challenging the notion that ownership is the only way to engage with fashion. Simultaneously, recycling and upcycling initiatives have become more sophisticated, with brands finding innovative ways to transform waste into new products.

Sustainable Fashion Market Growth

The sustainable fashion market has demonstrated significant financial growth in recent years, confirming that sustainability is not just an ethical imperative but also an economic opportunity. Recent figures indicate that the sustainable fashion industry is currently worth around $6.95 billion, with projections to reach $10.281 billion by 2025. Other reports suggest even more dramatic growth, with the ethical fashion space reaching a value of $7,548.2 million in 2022 and expected to grow at a CAGR of 8.1%, reaching a value of $16,819 million by 2032.

This growth is being driven by changing consumer preferences, with key statistics highlighting the shift:

- 77% of shoppers surveyed in a 2022 report by Drapers say they consider sustainability when buying fashion, either all the time or sometimes

- There has been a 50% rise in online searches for ‘second-hand clothing’ year-on-year from June 2021 to June 2022 in the UK

- A notable 75% of Gen Z respondents said that reducing consumption was one of their primary motivations for buying pre-owned clothes

- Around 73% of millennials are willing to pay extra to purchase items from sustainable brands

The Future of Sustainable Fashion: What’s Next?

Next-Generation Materials and Technologies

The future of sustainable fashion will likely be shaped by breakthroughs in materials science and production technologies. We’re already seeing early stages of biofabrication—growing materials in labs using biotechnology—which could eventually replace conventional agriculture and synthetic production methods. Companies are experimenting with leather grown from mushroom mycelium, spider silk produced by microbes, and dyes created from bacteria, pointing toward a future where fashion materials are engineered for sustainability from the molecular level up.

Digital fashion represents another frontier, with virtual clothing and augmented reality try-ons potentially reducing the environmental impact of overproduction and returns. While still in early stages, these technologies could eventually decouple the desire for novelty from physical production, allowing for expression and experimentation without material waste. The development of more sophisticated recycling technologies, particularly for blended fabrics, also holds promise for closing the loop on textile waste.

Regulatory Trends and Systemic Change

The future will likely see increased government regulation of the fashion industry’s environmental and social practices. The European Union has already begun implementing ambitious circular economy policies, and other regions are expected to follow with extended producer responsibility laws, mandatory due diligence requirements, and stricter regulations around green claims. This regulatory pressure will force industry-wide changes rather than relying on voluntary initiatives.

We’re also likely to see continued evolution in transparency and traceability technologies. Blockchain, DNA tagging, and other verification systems may become standard practices, allowing consumers to verify claims about a garment’s origins, materials, and production conditions. This could fundamentally reshape relationships between brands, suppliers, and consumers, making supply chains more visible and accountable.

Evolving Consumer Mental Models

Perhaps the most significant change will come from continued evolution in how consumers relate to clothing. The future may see a stronger embrace of sufficiency rather than efficiency—focusing on having “enough” rather than constantly seeking more. The concept of a “well-curated wardrobe” composed of durable, versatile, and repairable pieces may replace the current model of overflowing closets filled with rarely worn items.

The growing recognition of fashion as a service rather than a product—through rental, subscription, and sharing models—could also transform consumption patterns. As these alternatives become more convenient and appealing, ownership may become less central to how people engage with fashion. These shifts, combined with greater appreciation for craftsmanship, story, and emotional connection to clothing, point toward a future where fashion is valued differently—not just for its novelty or price, but for its sustainability, durability, and meaning.

Frequently Asked Questions

When did sustainable fashion become popular?

The sustainable fashion movement doesn’t have a single founder but rather emerged from various sources. Key early pioneers include:

- Hippie and punk subcultures of the 1960s-1970s, who rejected mass consumerism

- Katharine Hamnet, who began researching fashion’s ecological impact in 1989

- People Tree, founded in 1991, is one of the first dedicated sustainable fashion brands

- Patagonia, which pioneered recycled materials and switched to organic cotton in the 1990s

What is the difference between sustainable and ethical fashion?

- Sustainable fashion focuses primarily on environmental impacts—reducing pollution, resource use, and waste throughout a garment’s lifecycle

- Ethical fashion emphasizes social impacts—ensuring fair wages, safe working conditions, and human rights throughout the supply chain

Many brands and consumers now recognize that truly responsible fashion must address both environmental and social concerns.

How large is the sustainable fashion market today?

The sustainable fashion market has demonstrated impressive growth:

- Current worth is approximately $6.95 billion

- Projected to reach $10.281 billion by 2025

- Another report notes the ethical fashion market reached $7,548.2 million in 2022 and is expected to grow to $16,819 million by 2032

This growth is largely driven by millennials and Gen Z, who increasingly prioritize sustainability in their purchasing decisions.

What are the most important certifications for sustainable fashion?

- Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS): International standard for organic textiles

- Fair Trade Certified: Ensures fair wages and safe working conditions

- Global Recycled Standard: Verifies recycled content in products

These certifications help consumers identify genuinely sustainable and ethical products amidst often-confusing marketing claims.

How can consumers identify greenwashing in fashion?

- Looking for specific claims with evidence rather than vague terms like “eco-friendly”

- Checking for transparent supply chain information

- Researching whether brands publish comprehensive sustainability reports

- Verifying if products have recognized certifications like GOTS or Fair Trade

- Being skeptical of collection-level changes rather than company-wide sustainability initiatives

Conclusion

The journey to understand when sustainable fashion started reveals a movement that has evolved through decades of growing awareness, tragic events, pioneering innovations, and changing consumer values. From the counterculture movements of the 1960s and 1970s to the groundbreaking work of early sustainable designers in the 1980s and 1990s, from the wake-up call of the Rana Plaza tragedy to today’s technologically advanced solutions, sustainable fashion has developed into a powerful force reshaping the entire industry.

What began as a niche concern has grown into a multi-billion-dollar market with the potential to transform how clothing is designed, produced, sold, and valued. The history of sustainable fashion demonstrates that meaningful change is possible—that consumers, activists, designers, and businesses can collectively push an entire industry toward more responsible practices.

As we look to the future, it’s clear that the sustainable fashion movement will continue to evolve, facing new challenges and opportunities. Technological innovations, regulatory developments, and shifting consumer mindsets will all play roles in shaping what comes next. But the core principles—environmental responsibility, social justice, transparency, and circularity—will remain essential to creating a fashion industry that respects both people and the planet.

The question of when sustainable fashion started ultimately leads us to a more important question: where do we go from here? The answer will depend on the choices made by everyone connected to fashion—from designers to manufacturers, retailers to consumers. Each of us has a role to play in continuing the journey toward a more sustainable fashion future.